It is all the rage to say that the modern attention span is decreasing because of the online world.

What a load of tosh.

It is simply a way of blaming the audience for your failure to communicate.

What a load of tosh.

It is simply a way of blaming the audience for your failure to communicate.

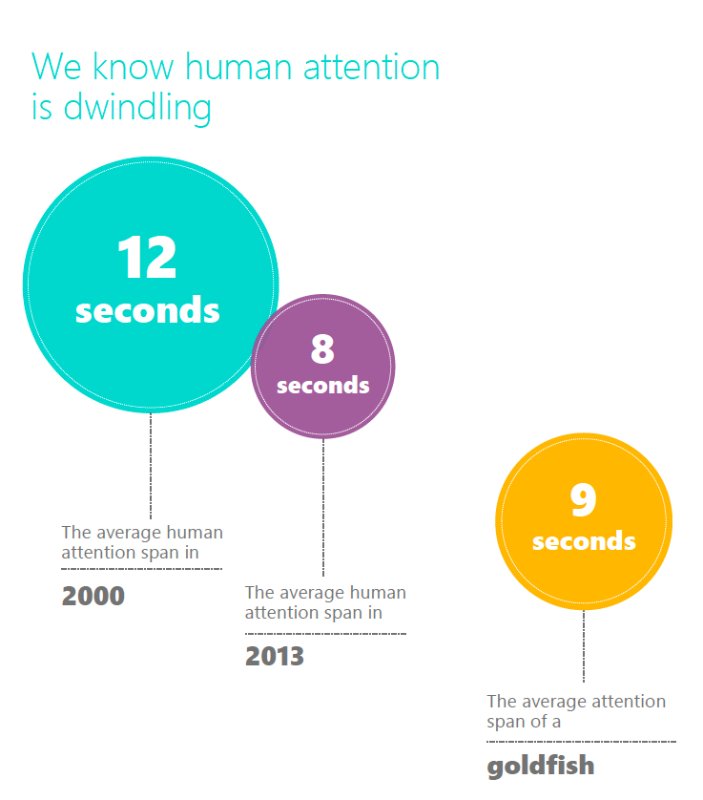

A balloon diagram full of hot air

The latest reason for rolling out the shorter attention span excuse for poor communication has been based on an unreferenced non-peer reviewed marketing report (pdf) by Microsoft that didn’t even manage to clearly define what attention span was, although it did categorise three types. While the report made some good, self evident, marketing points, it talks more about how attention shifts more quickly between technologies, not that attention span per se is declining.

In fact, the effort to multitask seems to be the real problem here. And no matter what we may like to believe about ourselves, science says nobody can multitask effectively.

The whole mess about attention span in this report came from a factoid in a balloon diagram (below) that was then used as a headline and lead sentence by multiple news outlets. The factoid was not even part of the research and it has been well and truly taken apart by Policyviz.

The latest reason for rolling out the shorter attention span excuse for poor communication has been based on an unreferenced non-peer reviewed marketing report (pdf) by Microsoft that didn’t even manage to clearly define what attention span was, although it did categorise three types. While the report made some good, self evident, marketing points, it talks more about how attention shifts more quickly between technologies, not that attention span per se is declining.

In fact, the effort to multitask seems to be the real problem here. And no matter what we may like to believe about ourselves, science says nobody can multitask effectively.

The whole mess about attention span in this report came from a factoid in a balloon diagram (below) that was then used as a headline and lead sentence by multiple news outlets. The factoid was not even part of the research and it has been well and truly taken apart by Policyviz.

The balloon diagram stated that human attention span was less than a goldfish – down from 12 secs in 2000 to 8 secs in 2013. Its reference? The non-peer reviewed, relatively unscientific Statistic Brain.

It also claimed a goldfish’s attention span was 9 secs. That last fact should have been an alarm bell to a half decent reporter. How do you measure the attention span of a goldfish?

The only research I’m aware of in this area is about goldfish memory and that, dear reader, has now been estimated as considerably more than 9 seconds, more like five months to a year.

The media have a lot to answer for, after failing to check the source of their headlines and spreading this rubbish far and wide.

But let’s get back to the supposed decline in attention spans.

Don’t blame attention span for two-minute videos

I don’t know how many times I have heard multimedia professionals say that videos should only be two minutes long or nobody will watch them. Yet blockbuster movies are either, depending on the figures you look at, increasing in length or about the same.

So at work we believe deeply that the public attention span is declining and can only handle two minutes of a video but then, come the weekend, we sit in a darkened cinema with hundreds of other people and watch a two-hour blockbuster, join millions binge-watching our favorite television show or play computer games for hours on end.

And don’t think this doesn't count because games, television and movies are entertainment. Attention span is simply a measure of how long you can focus on something singular and take it in. And anyway, if any of you have sat through an Adam Sandler movie you will know that sometimes entertainment isn’t even on the menu.

But let me present another example in a more formal situation.

My wife created a video for paramedic students about the course they would be doing that was 20 minutes long.

The marketing professionals who reviewed the video before it was sent to the students said that the video should be made shorter. If it couldn't be made shorter then the video should be sent with a letter that said (and this is a direct quote), "you should brace yourselves and get some popcorn because the video was important to watch but it was really, really long".

My wife and her colleagues refused to heed that advice.

When the students were surveyed there was one major complaint – it was too short. The students wanted more. Why? Because they were engaged, it was a priority.

Imagine how much they would have screamed if the video had been two minutes long.

What online statistics tell us

Often the idea that videos need to be shorter is based on video statistics drawn from YouTube or Facebook.

There is a lovely piece of data mining in an article by Reelseo, What’s the optimal length for a YouTube v Facebook video?, that looks at this and uses the idea of high engagement as the key indicator, although without exactly explaining what high engagement means. My guess is that it means the viewers watched around 80%-100% of the video.

The figures suggest on average that 2-3 minutes is the sweet spot for getting both high viewer numbers and viewers who will watch the video to the end.

Digging further down into the figures there is a suggestion that YouTube users have longer attention spans and they are more likely to watch videos longer than 15 minutes right to the end (unlike those “goldfish brains” on Facebook who clock out after 2.5 minutes). That would be a fine conclusion if they were two separate groups. The problem is the world is not filled with those who just use YouTube or just Facebook – the majority use both.

The difference in the length of engagement is probably because the two platforms are used differently.

You can see that in the fact that the average video length on You Tube is ten times as long as on Facebook (870 secs v 81 secs).

On YouTube music videos are the number one topic but a lot of people use it for instructional videos or for longer commentary pieces in an area where they have a particular area of interest.

For Facebook it’s all about sharing with friends. It’s often about the one liner, the small amusement, not about learning or getting a better understanding in an area of interest. Learning online in the context of videos is often about individual not shared activities.

Often what is not spelt out in these figures is whether the average length of time watching videos online takes into account bounce rates. In my video habits, when I’m searching for something I will quickly bounce in and out of a number of videos a few times before I find what I am after and settle in.

If I watch the first 5 seconds of a video and realize it’s not what I was after, I immediately go back and search again. That’s not short attention span, that’s decision making. But that activity, if included in the figures, is likely to drag down the average time spent watching videos.

And just a heads up here for marketers about video figures. Facebook defines video engagement as a viewer watching just 3 seconds of a natively uploaded video even if the sound isn't switched on, vastly inflating their engagement figures in their battle against YouTube

YouTube uses a much longer time to assess viewer engagement, usually 30 secs or greater.

There is a nice piece on that here.

But what do all these online video figures tell us about attention span? Certainly they are useful when it comes to helping us develop good video structures for marketing with the Call to Action upfront and at the end but in terms of attention span they tell us NOTHING.

Without knowing exactly why people are looking for the videos or how they are using them, we cannot draw any conclusions about attention span and we certainly can’t suggest attention spans are declining.

Old media and short attention spans

Let’s look back in time to get a sense of attention spans in the media. For decades in television and radio news broadcasts - well before the internet came along - each story was usually shorter than 2 minutes. Ditto for advertising.

That doesn’t mean that before the internet we had shorter attention spans either. It’s just this format works for broadcasting news when it is tied to a fixed time slot.

It’s the same with print. When we read print newspapers we look at headlines, first sentences and photographs to decide if we will read a story or not. Our eyes scan each page like a search engine seeking the stories that interest us.

When I worked with News Corp around a decade ago we estimated that readers only read 1 in 20 stories right to the end. This is not because they had short attention spans but because readers quickly worked out they weren’t interested in the other 19. They made their decisions early. That was the print bounce rate.

Today in the online world with all their analytics tools, online newspapers know exactly the level of engagement. I will chat about that in a later post.

For instance the analytics show that this long-form story The Big Sleep, from the Sydney Morning Herald has been read more than 1 million times right to the end.Months and months later, people still continue to be seriously engaged with it.

Based on the idea that modern attention spans are getting shorter, this story should never have achieved this readership.

Websites like Longform, which curates extended articles from around the world continue to thrive and when the next House of Cards comes out, viewers from around the world will watch it all in one sitting.

In light of this, our attention spans seem to be just fine.

The actual research around attention spans

What we do know, because it has been well researched, is that our attention slips in an out for a host of reasons as described and referenced very nicely by Saga Briggs in her article The science of attention: how to capture and hold the attention of easily distracted students.

Two authorities of multimedia learning, Mayer and Clark, have extensively researched the ways we learn and retain information. They recognize that attention drifts and have clearly spelt out great guidelines for maintaining focus in their book, E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. It’s the bible in the field of multimedia learning and much of it has been peer reviewed and tested.

The idea of declining attention span will not be found in this book because it is not a real issue.

When you look at all the research, the key factor for engagement, learning and retaining information is priority. It’s that old key communications rule, why should our audience care, except this time it is solidly supported by research.

Getting engagement and viewers is about understanding the priorities of your viewers.

If you tell a room full of students that they will be tested on everything they see in a video in the next half hour, watch the engagement level go up. They have at that point mentally prioritized the importance of paying attention for that period of time.

Nearly every educator around the world knows the phrase "assessment drives engagement".

When attention wanders it is because your audience no longer thinks what they are viewing or hearing is important to them. There are other priorities. Either that or you have missed key communication principals and they fail to recognize how important it is to them.

This is not an issue of declining attention spans, it’s about a failure to communicate well.

The whole idea of shrinking attention spans in the modern age should be thrown in the garbage alongside the bankrupt idea that there is a clearly defined Generation X, Y, Z or Millennials. It is time we called bullshit on these unproven ideas. They are all spin or gut feeling with no basis in reality.

There are good marketing reasons for making shorter videos but they have nothing to do with shrinking attention spans. If the audience you aimed to engage isn’t watching your videos, it’s not their fault. More likely you haven’t paid attention to their priorities.

It also claimed a goldfish’s attention span was 9 secs. That last fact should have been an alarm bell to a half decent reporter. How do you measure the attention span of a goldfish?

The only research I’m aware of in this area is about goldfish memory and that, dear reader, has now been estimated as considerably more than 9 seconds, more like five months to a year.

The media have a lot to answer for, after failing to check the source of their headlines and spreading this rubbish far and wide.

But let’s get back to the supposed decline in attention spans.

Don’t blame attention span for two-minute videos

I don’t know how many times I have heard multimedia professionals say that videos should only be two minutes long or nobody will watch them. Yet blockbuster movies are either, depending on the figures you look at, increasing in length or about the same.

So at work we believe deeply that the public attention span is declining and can only handle two minutes of a video but then, come the weekend, we sit in a darkened cinema with hundreds of other people and watch a two-hour blockbuster, join millions binge-watching our favorite television show or play computer games for hours on end.

And don’t think this doesn't count because games, television and movies are entertainment. Attention span is simply a measure of how long you can focus on something singular and take it in. And anyway, if any of you have sat through an Adam Sandler movie you will know that sometimes entertainment isn’t even on the menu.

But let me present another example in a more formal situation.

My wife created a video for paramedic students about the course they would be doing that was 20 minutes long.

The marketing professionals who reviewed the video before it was sent to the students said that the video should be made shorter. If it couldn't be made shorter then the video should be sent with a letter that said (and this is a direct quote), "you should brace yourselves and get some popcorn because the video was important to watch but it was really, really long".

My wife and her colleagues refused to heed that advice.

When the students were surveyed there was one major complaint – it was too short. The students wanted more. Why? Because they were engaged, it was a priority.

Imagine how much they would have screamed if the video had been two minutes long.

What online statistics tell us

Often the idea that videos need to be shorter is based on video statistics drawn from YouTube or Facebook.

There is a lovely piece of data mining in an article by Reelseo, What’s the optimal length for a YouTube v Facebook video?, that looks at this and uses the idea of high engagement as the key indicator, although without exactly explaining what high engagement means. My guess is that it means the viewers watched around 80%-100% of the video.

The figures suggest on average that 2-3 minutes is the sweet spot for getting both high viewer numbers and viewers who will watch the video to the end.

Digging further down into the figures there is a suggestion that YouTube users have longer attention spans and they are more likely to watch videos longer than 15 minutes right to the end (unlike those “goldfish brains” on Facebook who clock out after 2.5 minutes). That would be a fine conclusion if they were two separate groups. The problem is the world is not filled with those who just use YouTube or just Facebook – the majority use both.

The difference in the length of engagement is probably because the two platforms are used differently.

You can see that in the fact that the average video length on You Tube is ten times as long as on Facebook (870 secs v 81 secs).

On YouTube music videos are the number one topic but a lot of people use it for instructional videos or for longer commentary pieces in an area where they have a particular area of interest.

For Facebook it’s all about sharing with friends. It’s often about the one liner, the small amusement, not about learning or getting a better understanding in an area of interest. Learning online in the context of videos is often about individual not shared activities.

Often what is not spelt out in these figures is whether the average length of time watching videos online takes into account bounce rates. In my video habits, when I’m searching for something I will quickly bounce in and out of a number of videos a few times before I find what I am after and settle in.

If I watch the first 5 seconds of a video and realize it’s not what I was after, I immediately go back and search again. That’s not short attention span, that’s decision making. But that activity, if included in the figures, is likely to drag down the average time spent watching videos.

And just a heads up here for marketers about video figures. Facebook defines video engagement as a viewer watching just 3 seconds of a natively uploaded video even if the sound isn't switched on, vastly inflating their engagement figures in their battle against YouTube

YouTube uses a much longer time to assess viewer engagement, usually 30 secs or greater.

There is a nice piece on that here.

But what do all these online video figures tell us about attention span? Certainly they are useful when it comes to helping us develop good video structures for marketing with the Call to Action upfront and at the end but in terms of attention span they tell us NOTHING.

Without knowing exactly why people are looking for the videos or how they are using them, we cannot draw any conclusions about attention span and we certainly can’t suggest attention spans are declining.

Old media and short attention spans

Let’s look back in time to get a sense of attention spans in the media. For decades in television and radio news broadcasts - well before the internet came along - each story was usually shorter than 2 minutes. Ditto for advertising.

That doesn’t mean that before the internet we had shorter attention spans either. It’s just this format works for broadcasting news when it is tied to a fixed time slot.

It’s the same with print. When we read print newspapers we look at headlines, first sentences and photographs to decide if we will read a story or not. Our eyes scan each page like a search engine seeking the stories that interest us.

When I worked with News Corp around a decade ago we estimated that readers only read 1 in 20 stories right to the end. This is not because they had short attention spans but because readers quickly worked out they weren’t interested in the other 19. They made their decisions early. That was the print bounce rate.

Today in the online world with all their analytics tools, online newspapers know exactly the level of engagement. I will chat about that in a later post.

For instance the analytics show that this long-form story The Big Sleep, from the Sydney Morning Herald has been read more than 1 million times right to the end.Months and months later, people still continue to be seriously engaged with it.

Based on the idea that modern attention spans are getting shorter, this story should never have achieved this readership.

Websites like Longform, which curates extended articles from around the world continue to thrive and when the next House of Cards comes out, viewers from around the world will watch it all in one sitting.

In light of this, our attention spans seem to be just fine.

The actual research around attention spans

What we do know, because it has been well researched, is that our attention slips in an out for a host of reasons as described and referenced very nicely by Saga Briggs in her article The science of attention: how to capture and hold the attention of easily distracted students.

Two authorities of multimedia learning, Mayer and Clark, have extensively researched the ways we learn and retain information. They recognize that attention drifts and have clearly spelt out great guidelines for maintaining focus in their book, E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. It’s the bible in the field of multimedia learning and much of it has been peer reviewed and tested.

The idea of declining attention span will not be found in this book because it is not a real issue.

When you look at all the research, the key factor for engagement, learning and retaining information is priority. It’s that old key communications rule, why should our audience care, except this time it is solidly supported by research.

Getting engagement and viewers is about understanding the priorities of your viewers.

If you tell a room full of students that they will be tested on everything they see in a video in the next half hour, watch the engagement level go up. They have at that point mentally prioritized the importance of paying attention for that period of time.

Nearly every educator around the world knows the phrase "assessment drives engagement".

When attention wanders it is because your audience no longer thinks what they are viewing or hearing is important to them. There are other priorities. Either that or you have missed key communication principals and they fail to recognize how important it is to them.

This is not an issue of declining attention spans, it’s about a failure to communicate well.

The whole idea of shrinking attention spans in the modern age should be thrown in the garbage alongside the bankrupt idea that there is a clearly defined Generation X, Y, Z or Millennials. It is time we called bullshit on these unproven ideas. They are all spin or gut feeling with no basis in reality.

There are good marketing reasons for making shorter videos but they have nothing to do with shrinking attention spans. If the audience you aimed to engage isn’t watching your videos, it’s not their fault. More likely you haven’t paid attention to their priorities.